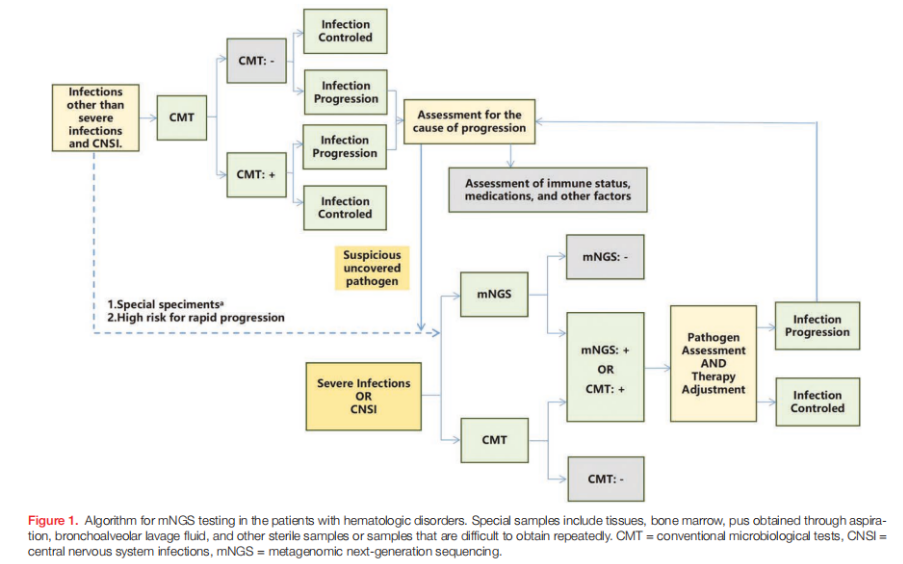

The 2024 China Expert Consensus on metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) in hematological disorders, published in Blood Science, offers the first national guidance on how mNGS should be applied to infection diagnosis in this highly vulnerable population. Because hematological diseases and their treatments cause profound immunosuppression, infections remain a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Traditional microbiological tests (CMTs) frequently produce delayed or negative results, especially after antibiotic exposure. mNGS, which enables broad, unbiased pathogen detection, has therefore become an essential complementary tool.

Clinical Indications

The consensus emphasizes that mNGS should complement, not replace, standard diagnostic methods. It is recommended when CMTs are inconclusive, symptoms persist despite empirical therapy, or rare, mixed, or atypical infections are suspected. Conditions where mNGS has demonstrated clear value include febrile neutropenia, bloodstream infections, lower respiratory tract infections, central nervous system infections, gastrointestinal infections, skin and soft tissue infections, and urinary tract infections.

In febrile neutropenia, mNGS can identify pathogens suppressed by prior antibiotics that blood cultures often fail to detect. For respiratory infections, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) is preferred over sputum because it reduces interference from colonizing organisms and improves diagnostic accuracy. Cerebrospinal fluid remains the specimen of choice for suspected central nervous system involvement. Across clinical scenarios, the consensus urges clinicians to interpret mNGS results alongside immune status, imaging, laboratory findings, and the patient’s overall clinical trajectory.

(Blood Science. 7(3):e00241, September 2025.)

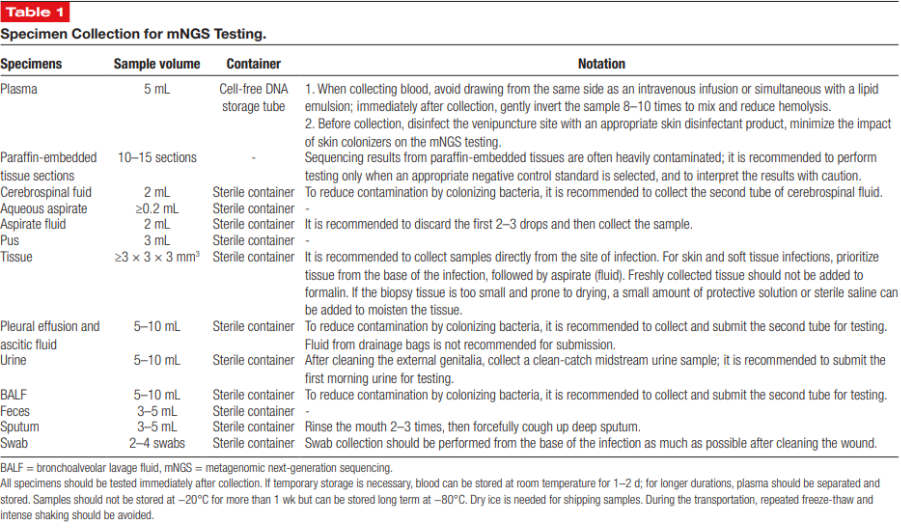

Sample Collection and Quality Control

Reliable mNGS results depend heavily on proper specimen collection and handling. The consensus provides specific volume requirements: 5 mL of plasma, at least 2 mL of CSF, 5–10 mL of BALF, 3 mL of pus, and tissue samples measuring at least 3 × 3 × 3 mm. Strict aseptic technique is essential. For fluids such as CSF, BALF, or aspirates, the first few drops should be discarded to reduce contamination from skin or environmental flora. Drainage fluids should not be used because they do not accurately reflect true infection sites.

Specimens should be processed promptly; if delays are unavoidable, freezing at –80 °C is recommended to maintain nucleic acid stability. Paraffin-embedded specimens may contain contaminants and must be interpreted cautiously. For sputum, patients should rinse their mouth before collection to minimize interference from oral microbes. These quality-control measures help prevent false positives and ensure diagnostic reliability.

(Blood Science. 7(3):e00241, September 2025.)

Interpretation of Results

The consensus stresses that mNGS results must be evaluated in the clinical context. Detection of microbial DNA alone does not prove active infection, as some organisms may represent colonization or contamination. Conversely, a negative result does not rule out infection when pathogen load is low or sampling is inadequate. Read counts, genome coverage, and relative abundance help differentiate true pathogens from background signals.

The guideline categorizes organisms based on their pathogenic significance in plasma, respiratory fluids, and CSF. Highly pathogenic bacteria and fungi generally carry strong diagnostic weight, whereas some organisms require careful interpretation as opportunists. Viral detections—especially in post-transplant patients—may represent latent or reactivated infections rather than primary disease. Immune status, prior antimicrobial therapy, and timing after transplantation should all be considered when assessing the clinical relevance of reported organisms.

Advantages and Limitations

mNGS offers comprehensive pathogen detection, rapid turnaround, and high sensitivity in patients who have already received antimicrobials. It is particularly effective for identifying polymicrobial infections, fastidious organisms, and certain antimicrobial resistance genes. However, mNGS is primarily qualitative, relatively costly, and vulnerable to contamination. Sensitivity may vary across pathogen types, especially for RNA viruses unless RNA sequencing is specifically included. Expert interpretation remains essential to avoid misdiagnosis.

Conclusion

The 2024 China Expert Consensus provides clear, standardized guidance for incorporating mNGS into the diagnostic evaluation of infections in hematology. It outlines when mNGS is appropriate, how specimens should be collected, and how results should be interpreted within the broader clinical picture. While CMTs remain foundational, mNGS serves as a crucial adjunct for detecting pathogens in complex, persistent, or polymicrobial infections, ultimately improving diagnostic accuracy and patient outcomes.

Click the link to view the original article: