Editor’s Note: The 21st National Conference on Viral Hepatitis and Hepatology, and the Annual Meetings of the Chinese Society of Hepatology and the Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases, took place from December 22nd to 24th, 2023, in Chengdu, Sichuan Province. This conference, co-hosted by the Chinese Medical Association, the Chinese Society of Hepatology, and the Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases, and organized by the Sichuan Medical Association, showcased the latest developments and hot topics in the research of viral hepatitis, hepatology, and infectious diseases. During the event, Dr. Jie Li from Nanjing University Medical School’s Drum Tower Hospital shared insights on the comorbidity and management of diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The following is a summary of her presentation.

- Epidemiology of NAFLD

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is currently the most common chronic liver disease worldwide. Dr Jie Li’s research team found that the prevalence of NAFLD in Asian adults is 29.63%, showing an upward trend. High-risk factors for the incidence of NAFLD include male gender (37.11%), advanced age (32.23%), obesity (52.3%), and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) (52.4%)[1]. Another meta-analysis in mainland China indicated an overall NAFLD prevalence of 29.88%, with rates in males (34.75%), postmenopausal females (34.52%), and the 50-59 age group (29.14%). The prevalence of NAFLD in patients with T2DM and obesity was 51.83% and 66.21%, respectively. Geographically, the northern regions showed the highest prevalence, while the southwestern areas demonstrated the lowest[2].

NAFLD is a metabolic disease affecting multiple systems, intricately linked to insulin resistance and systemic metabolic inflammation. The main causes of death in NAFLD patients are cardiovascular disease, extrahepatic malignancies, T2DM, chronic kidney disease, and liver-related complications[3].

- Rebranding of NAFLD Emphasizes the Dominant Role of Metabolic Abnormalities

With the global rise of obesity and diabetes, the limitations of the exclusive diagnostic term “NAFLD” have become apparent. In 2020, an international group of NAFLD experts proposed renaming NAFLD and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) to metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), respectively.

The new diagnostic criteria for MAFLD are based on evidence of hepatic steatosis (histology, non-invasive biomarkers, or imaging) and one of the following three conditions: overweight or obesity, T2DM, or the presence of two or more metabolic dysfunctions. This “positive” diagnostic criterion is driven by metabolic dysfunctions, without considering alcohol consumption or other concurrent liver diseases. Abundant evidence suggests that[4-6] early overweight and obesity increase the risk of severe liver disease by 1.49 and 2.17 times in males, respectively. The risk of developing severe liver disease is even higher in obese individuals with T2DM compared with obese ones without T2DM, increasing by 3.28 and 1.72 times, respectively. Patients with fatty liver and hypertension or dyslipidemia have a 1.8 times higher risk of progressing to cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), while those with T2DM, obesity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension face a 2.6 times higher risk. Therefore, metabolic dysfunctions such as T2DM, obesity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension are not only important causes of fatty liver disease but also risk factors for adverse outcomes.

However, the new definition of MAFLD faced opposition from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and pharmaceutical companies developing new drugs for NASH. In June 2023, AASLD and the European Association for the Study of the Liver released the “Delphi Consensus of Multiple Societies on the New Naming of Fatty Liver Disease,” proposing to rename NAFLD as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) and recognizing the importance of NASH, suggesting renaming it metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH). MASLD includes patients with hepatic steatosis and at least one of five cardiovascular metabolic risk factors. Those without metabolic risk factors and factors causing fatty liver are referred to as cryptogenic steatotic liver disease (cryptogenic SLD). In addition to MASLD, a new category named MetALD is proposed to describe MASLD patients with significant alcohol consumption (≥140g ethanol/week for females and ≥210g ethanol/week for males)[7].

- Comorbidity of Fatty Liver and Diabetes

Fatty liver and diabetes share common pathophysiological mechanisms. Insulin resistance is the initiating factor for diabetes and a core pathogenic mechanism for fatty liver. It leads to decreased peripheral glucose uptake, increased lipid breakdown, a rapid rise in serum free fatty acids (FFA), increased FFA uptake by the liver, and changes in various regulatory factors, including signals derived from intestinal nutrition, fat factors, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, ultimately leading to the development of NAFLD[8].

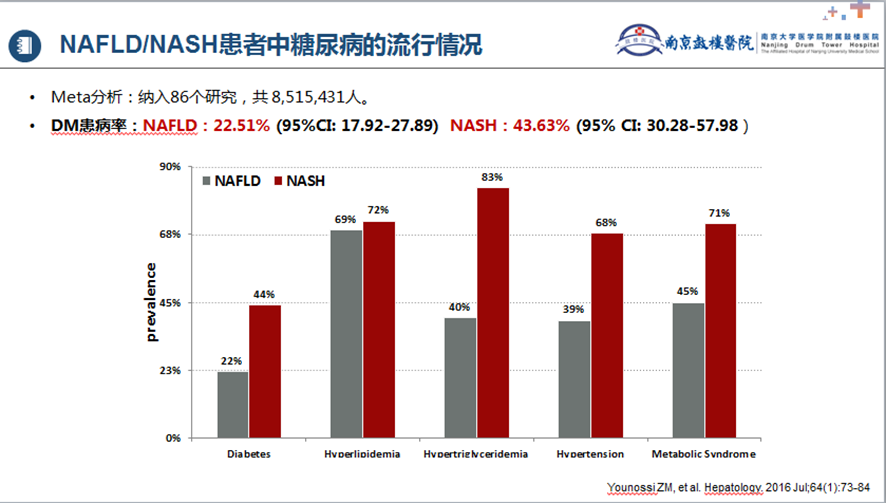

Fatty liver and diabetes are mutually causal. A meta-analysis[9] including 33 studies with 501,022 individuals (30.08% with NAFLD) and a median follow-up of 5 years found that NAFLD patients had a higher risk of developing Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) (HR=2.19, 95% CI: 1.93-2.48), with a higher risk as NAFLD severity increased (HR=2.69, 95% CI: 2.08-3.49). Another meta-analysis by Younossi et al.[10], covering 86 studies with 8,515,431 individuals, reported T2DM prevalence in NAFLD/NASH patients of 22.51% (95% CI: 17.92-27.89) and 43.63% (95% CI: 30.28-57.98), respectively. Epidemiological studies on the comorbidity of NAFLD/NASH in adults with T2DM indicated NAFLD and NASH prevalence of 65.04% and 31.55%, respectively. Notably, in T2DM patients with concomitant NAFLD, the rates of significant fibrosis (F2-F4) were 35.54%, and advanced liver fibrosis (F3-F4) was 14.95%.

Figure 1. Prevalence of Diabetes in NAFLD/NASH Patients

Diabetic patients with normal liver enzymes may still exhibit severe liver fibrosis. A French study[12] included 561 patients with controlled Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM), visiting primary care or endocrine clinics with normal transaminase levels. Controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) and vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE) were used for assessment. The results showed that 70% of the patients had hepatic steatosis, and 21% had liver fibrosis. Interestingly, only 28% of patients with severe liver fibrosis had abnormal liver enzymes.

Diabetes increases the risk of NAFLD patients developing liver cirrhosis, HCC, and tumors. A retrospective study in the United States[13] included 202,319 NAFLD patients from 130 hospitals between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2008, with follow-up until December 31, 2018. In the 3-year landmark analysis, 473 patients progressed to HCC, with an incidence rate of 0.28/1,000 person-years (PY) (95% CI, 0.26, 0.31). NAFLD patients with concurrent T2DM had a higher risk of HCC (HR: 2.65) and HCC/cirrhosis (HR: 2.46). In a Swedish study[14], 8,892 patients confirmed with NAFLD through biopsy between 1966 and 2016 were compared with a control group of 39,907 individuals matched for age, gender, region, and other factors. With a median follow-up of 13.8 years, 1,691 NAFLD patients developed tumors. Compared to the control group, NAFLD patients had a 1.27 times higher overall tumor incidence (10.9 vs. 13.8 per 1,000 person-years), primarily due to HCC (HR: 17.08). Therefore, the presence of diabetes increases the risk of tumor occurrence in NAFLD patients with cirrhosis.

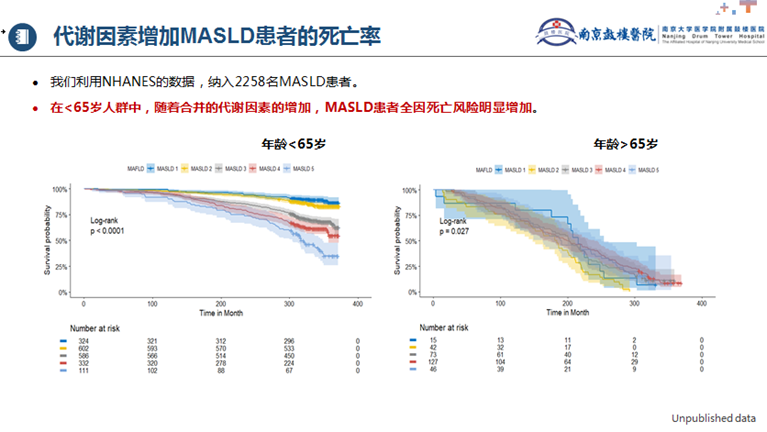

Diabetes and metabolic factors contribute to increased mortality in MAFLD patients. In the latest study by Professor Li Jie’s team[15], 4,559 MAFLD patients (30.8%), including 25.5% with T2DM, were included. The research revealed that concurrent T2DM was associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality (HR: 1.427) and cardiovascular-related mortality (HR: 1.458). Another unpublished study included 2,258 MASLD patients. In individuals under 65 years old, the risk of all-cause mortality in MASLD patients significantly increased with the addition of concurrent metabolic factors (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Metabolic Factors Increase Mortality in MASLD Patients

Combining diabetes increases the risk of disease progression in patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) and fatty liver (FL). Dr. Jie Li’s team[16] conducted a study involving 869 treatment-naive CHB patients with concomitant FL who underwent liver biopsy in four provinces in China (Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Henan) and eight medical centers between 2004 and 2020. In the CHB combined with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) group, patients with concurrent Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) had a significantly higher risk of liver inflammation and fibrosis compared to those without T2DM. This association was independent of age, gender, hepatic steatosis, other metabolic factors (such as BMI), and virological factors. Additionally, a non-invasive model, PPDHG (PLT/PT/Diabetes/HBeAg/GLB), was established based on a multicenter liver biopsy cohort of CHB combined with NAFLD patients to predict significant liver fibrosis.

PPDHG Formula(PLT/PT/Diabetes/HBeAg/GLB): -8.773 – 0.008 × PLT + 0.569 × PT + 1.697 × diabetes (yes = 1, no = 0) + 0.611 × HBeAg (positive=1, negative=0) + 0.063 × GLB[17]. In another recent study by the team[18], using NHANES data, 2,803 T2DM patients were included, of which 1,903 (67.9%) were diagnosed with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) by ultrasound. The results indicated that T2DM patients with FIB-4 ≥ 1.3 and no severe hepatic steatosis had a higher risk of all-cause mortality (HR: 2.115).

- Management of Fatty Liver and Diabetes — Collaborative Approach

The diagnosis and treatment of MAFLD revolve around “metabolic dysfunction”. MAFLD is more efficient in identifying patients with significant liver fibrosis and a higher risk of disease progression than NAFLD. MAFLD patients have higher liver stiffness values than NAFLD patients. MAFLD is better at identifying the worsening cardiovascular disease risk and chronic kidney disease in patients. The prevalence and severity of obstructive sleep apnea are higher in MAFLD patients[19]. The APASL 2020 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of MAFLD[20] recommend considering ultrasound screening for MAFLD in high-risk populations such as overweight/obese individuals, those with T2DM, and metabolic syndrome. MAFLD patients should be assessed for other components of metabolic syndrome and receive appropriate treatment. Cardiovascular disease risk should be assessed, and patients should be referred to cardiology specialists when necessary. Diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes should be carried out to reduce the risk of cardiovascular and kidney diseases. As MAFLD often coexists with other liver diseases, the treatment should align with the recommendations for each specific disease. The guidelines emphasize the importance of screening high-risk populations for MAFLD, managing intra- and extra-hepatic diseases in collaboration, and the need for a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach.

The AASLD 2023 clinical guidance for NAFLD patients[21-22] points out that T2DM increases the risk of NASH and advanced fibrosis in NAFLD patients, requiring screening for advanced liver fibrosis. Patients with NASH-related advanced fibrosis typically have normal alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, making it inappropriate to exclude the possibility of advanced NASH based solely on normal ALT levels. NAFLD patients with FIB-4 ≥ 1.3 can use non-invasive methods such as liver transient elastography, magnetic resonance elastography, or enhanced liver fibrosis index to exclude advanced liver fibrosis.

In China, experts in the field have gradually formed consensus on the “blood glucose management in patients with cirrhosis and diabetes” and “management of type 2 diabetes complicated with NAFLD in Chinese adults.” The treatment and management of diabetes complicated with NAFLD primarily focus on three aspects. Firstly, improving metabolic abnormalities such as weight issues, T2D/high blood sugar, hypertension, and dyslipidemia associated with metabolic syndrome. Secondly, targeting liver-related treatment for NASH and fibrosis, reducing liver stiffness and hepatic fat content, improving relevant biomarkers, and alleviating liver fibrosis and NASH. Finally, improving major liver-related outcome events such as progression to cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis events, liver transplantation, hepatocellular carcinoma, or liver-related death/all-cause mortality. Enhancing major cardiovascular-related outcome events such as cardiovascular death, stroke, and heart attack is also crucial. The “Management Expert Consensus for Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Complicated with NAFLD in China” recommends establishing multidisciplinary teams for long-term effective management of patients with T2DM complicated with NAFLD. The comprehensive management of diabetes-fatty liver involves collaboration between general practitioners and specialists, focusing on patient-centric care, screening high-risk populations, and implementing graded diagnosis and treatment through multidisciplinary management.

- Exploration of Whole-Specialty Model

Based on the evidence and expert consensus mentioned above, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, affiliated with Nanjing Medical University, has initiated a model of collaboration between comprehensive hospitals and grassroots medical institutions to address the challenges posed by fatty liver disease. The hospital is exploring a comprehensive clinical pathway for the screening, diagnosis, and management of fatty liver, aiming to elevate the diagnostic and treatment capabilities of grassroots doctors, establish standardized criteria for the diagnosis and treatment of fatty liver at the grassroots level, enhance awareness among grassroots doctors for screening and managing fatty liver patients, and improve patient treatment rates.

The hospital is extending its services into the community by establishing community clinics for fatty liver, conducting screening and management for high-risk populations in the community, identifying patients in need of treatment, and referring them to comprehensive hospitals with fatty liver disease centers and corresponding disease specialists. Further, the hospital is strengthening the construction of standardized training bases for fatty liver whole-specialty diagnosis and treatment, continually enhancing the capacity of standardized management in community hospitals. The first “Standardized Diagnosis and Treatment Training Course for Fatty Liver Whole-Specialty” was successfully held in December, with Dr. Jie Li emphasizing that the goal of this training course is to establish a comprehensive specialty diagnosis and treatment system for fatty liver disease, enhance interaction between comprehensive hospitals and community hospitals, especially in the field of fatty liver and related metabolic diseases, and promote the standardization of diagnosis and treatment in community hospitals.

With the increasing prevalence of metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes, the incidence of MAFLD is steadily rising. Due to the lack of large-scale epidemiological studies and differences in diagnostic methods, the exact prevalence of MAFLD in the diabetic population is challenging to determine. For high-risk populations such as overweight/obese individuals, those with T2DM, and metabolic syndrome, ultrasound screening for MAFLD should be considered. Since there are currently no approved drugs for treating MAFLD, management focuses on lifestyle and dietary adjustments. Additionally, MAFLD patients should be assessed for other components of metabolic syndrome and receive corresponding treatment. It is recommended to establish multidisciplinary teams for long-term effective management of patients with T2DM complicated with NAFLD.

References:

[1] Jie Li / Mindie H, et al. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2019 May.

[2] Yuankai Wu, Qi Zheng, et al. Hepatol Int. 2020 Mar 4.

[3] Christopher D Byrne, Giovanni Targher. Journal of Hepatology 2015 Apr.

[4] Eslam M, et al. J Hepatol. 2020 Jul;73(1): 202-209.

[5] Eslam M, et al. Hepatol Int. 2020 Dec 14(6):889-919.

[6] Gallego-Durán R,et al. Front Immunol. 2021 Nov. 24.

[7] Rinella ME et al. J Hepatol. 2023 Jun 20:S0168-8278(23).

[8] Targher G, et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Sep 18(9):599-612.

[9] Mantovani A, et al. Gut. 2021 May;70(5):962-969.

[10] Younossi ZM, et al. Hepatology. 2016 Jul;64(1):73-84.

[11] En Li Cho E et al. Gut. 2023 Jul 25:gutjnl-2023-330110.

[12] Lomonaco et al. Diabetes Care. 2021 Feb;44(2):399-406.

[13] Cholankeril G, et al. J Hepatol. 2022 Nov 16.

[14] Simon TG, et al. Hepatology.2021 Nov;74(5):2410-2423.

[15] Zhu Y / Jie Li (Corresponding), et al. J Pers Med. 2023 Mar 20;13(3):554.

[16] Li J, et al. Hepatol Int (2023) 17:S104. APASL 2022 Oral.

[17] Li J, et al. J Viral Hepat. 2023 Apr;30(4):287-296

[18] Jie Li (Corresponding), et al. Hepatology International. 2023

[19] Jie Li (Corresponding), et al. Infectious Microbes & Diseases. 2022 Jun.

[20] Eslam M, et al. Hepatol Int. 2020 Dec;14(6):889-919.

[21] 倪文婧, 李婕, 范建高. 临床肝胆病杂志. 2023.

[22] Rinella E, et al. Hepatology 2023 May 1.

Expert Profile – Dr Jie Li

Administrative Director, Department of Infectious Diseases, Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital, Nanjing University Medical School

Executive Vice Director, Permanent Vice President, Nanjing University Institute of Viral and Infectious Diseases

Chief Physician, Researcher, Professor, Doctoral Supervisor